Since 2007, Spongelab Interactive has been working in the IT-based education field, notably developing games which have received positive feedback from students and experts alike.

With its latest release entitled History of Biology, the Canadian company is now getting students to take a look at some of the great moments in the advancement of biology. Game Forward had the opportunity to evaluate the game and to speak with one of the co-founders of Spongelab, Dr. Jeremy Friedberg.

Armed with a doctorate in molecular genetics and biotechnology, Dr. Friedberg has also been extensively involved in scientific education outreach programs and a teacher for over ten years. This experience has taught him many tricks to teaching and stimulating students when it comes to STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) education.

Wanting to inspire young gamers to explore the world of science and biology, Spongelab based its approach on the need to integrate technology in the classroom. Through its games, Spongelab translates sometimes complex scientific material into easy-to-grasp, bite-sized lessons with the help interactive media.

In Friedberg’s opinion, game-based learning is more important than ever. “Along the way, people realised that it can be challenging to teach creativity and critical thinking. But we can create an environment that allows creativity to occur and help foster it.”

A key element in the ‘21st Century learning’ philosophy, game-based education has been used to various degrees since the 1960s. “Think only of flight simulation,” highlights Dr. Friedberg. “This hands-on experience allows users to practice reacting to random crises in a simulated environment. [Pilots] have to be creative and critical in emergency situations, when they do not expect it. This helps determine if they can use the information stored in their minds in times of crisis and figure out what to do.”

What makes game-based learning different from traditional textbooks and lectures, aside from being more entertaining and engaging, is that it allows for teaching and assessment at one time. It puts users in a realistic situation and evaluates their knowledge over time. Today, game-based learning is increasingly used in medical and surgical training, and a number of other fields such as military training, linguistics and even customer relations.

In History of Biology, Spongelab is using the power human drama to arouse the natural curiosity of students and teach them about historical moments in the advancement of biology. “Students get hooked on and very interested in the story,” Dr. Friedberg says about the game.

“More than just giving students facts, it puts them into context. It follows the rich, vivid story of characters as regular and flawed individuals, not monoliths of science. They had motivations behind their discoveries, and the game shows the political and social context around these characters. Stories told are sometimes sad, but real.”

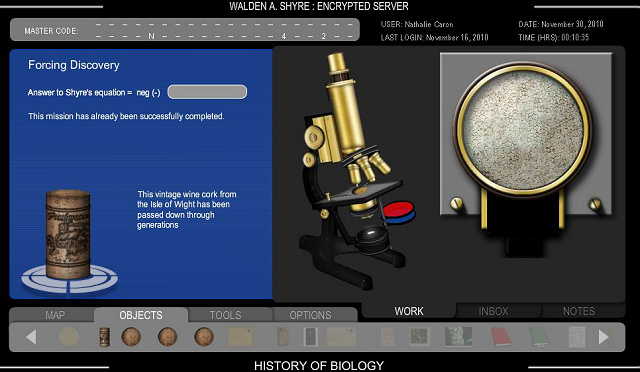

Targeting students ranging from high school seniors to college juniors, the game introduces players to Dr. Shyre, a synthetic biochemist on the cusp of a major milestone in biology research. Players act as Shyre’s research assistant, who has gone into hiding but provides instructions via automated emails. Shyre has hidden his discovery from watchful eyes and asks for players to help uncover it through a series of scavenger-hunt puzzles based on groundbreaking discoveries in biology.

While some of the concepts presented are complex, the game can also reach younger audiences. Referring to a pilot project with a grade 8 class, Friedberg explains that students have a harder time solving the puzzles but usually succeeded with a little help from their teachers, staying motivated by the game’s captivating story. He also notes significant interest in the mainstream gaming community.

When used in a classroom setting, teachers have the ability to adapt the game’s workflow by checking off the weekly distribution of missions. While students are encouraged to work together, the solutions to each puzzle are randomized—meaning that no two students pull the same information. They can share problem-solving techniques, but not answers. The full version includes a teaching guide providing mission-by-mission solving tips and learning objectives for the game’s 14 levels.

History of Biology has two sides. The main interface is built around a computer workstation where students receive problems and use tools to solve them. However, players must also make use of the Internet to scavenge additional information required. For example, one mission asks students to view an online version of Robert Hooke’s Micrographia and use clues found within to answer a riddle. Using outside sources adds an interesting dimension to the game, pushing students to be crafty and pay close attention to details.

Having had the chance to demo the first three levels of the game, the quality of its production and presentation are outstanding. Excellent voice-overs, attractive looking graphics, an inspiring soundtrack and a smooth-running engine enhance the game’s rich educational content.

My main concern came with the difficulty of the puzzles. The tools to solve them are all available in some way, but understanding what exactly you are looking for can be quite challenging. In that context, the game strongly benefits from the guidance of a teacher with access to the manual which outlines the steps to follow. Creative thinking is essential to successfully getting through the game.

While History of Biology is presented as story-based game, Spongelab employs other methods to present different types of information. In its previous release entitled Genomics Digital Lab, Spongelab takes a more traditional approach. Although gaming remains central, Genomics Digital Lab is presented in chapters, exploring learning objectives in sections.

“We spent time looking at different types of game design to determine which is most effective for particular content,” said Friedberg. “The choice of design was based on what was practical in an educational environment. The information is broken down to make it easier to share with students in limited class time, by portioning content. The game style includes visual puzzles where students learn the relative relationship between shapes representing chemicals in a reaction, for example.”

“We also had to understand the classroom environment and give teachers the ability to assess students as well as an integrated reporting system including formative and summative feedback,” added Dr. Friedberg. Genomics Digital Lab was in fact the first title to use the company’s online deployment and assessment system, successfully managing many limitations found in the typical classroom.

“We had to work around technical constraints to make it a browser-based application requiring no installation, working on minimal specs, and accessible through secure networks. This 1.5Gb game uses universally accessible technology which can even run through dial-up Internet service.” With its unique deployment system, Spongelab games can be played on virtually any Internet-ready platform.

The game’s target age group starts around grade 8, with the goal of having students continue to use it year after year. The content begins superficially, but offers students more layers of detail over time. A recent study (PDF) from York University evaluated Genomics Digital Lab’s success rates with students between grades 9 and 12. It found that in more than half of the cases, their tests scores improved after playing the game and strongly recommended the software as a test review tool.

Based on a core curriculum which is universally taught, teachers can also tune the game to specific lesson plans. New lesson plans are still being added, currently reflecting all of Canada’s regional curriculums and about half of those from the United States. “We are sensitive to localizing content and have different language options, from American to British English to a variety of other languages,” Friedberg said.

These days, Spongelab is mainly working on creating content for four new real-time strategy titles—where players will manage different aspects of biology—and on developing a new content deployment system. However, as Dr. Friedberg explains, the company is also considering the possibility of tackling other subject matters. “We absolutely see ourselves permeating to other areas. Right now we see a need to focus on STEM. But for example, History of Biology pulls from every subject, from STEM and literacy to history and art. The historical model is a framework that can be applied and replicated for any subject.”

Looking further ahead to the growing role of educational games in schools, the company is seeing a small revolution. Classroom technology is changing rapidly with the introduction of open wireless broadband Internet and better computers. With the advent of small devices like portable tablets, Spongelab sees a lot of potential and is hopeful that content will eventually catch up. However, the classroom environment will need to be as strong as the technology available.

“The public education system will need to do more keep up, having more computers in the classroom, allowing content to be deployed through these devices,” finds Dr. Friedberg. “But this requires a different business model. Traditional textbooks have a life of about five years, tablet PCs can’t work the same way. Each student would be required to have a personal one as part of their school supplies. There is of course a socio-economic problem where the government would have to step in so that all students can be on equal footing.”

Despite missing some pieces that would allow game-based education to become the norm, companies like Spongelab continue to make headway. Reaching thousands of users in 65 countries around the world, Spongelab has made a name for itself through its content-rich and visually appealing STEM games.